Introductory notes written for the booklet of my first recording of Triadic Memories by Morton Feldman (Sub Rosa, 1990).

At the end of the forties, when young American composers, John Cage, Earle Brown, David Tudor and Morton Feldman among them, decided to act upon the ramifications of the dissolution of the tonal system, they embarked upon an entirely different course than the European composers. The later, set on redefining a syntactic system that would allow the re-legitimation of a structural approach, ushered in total serialism, a new step towards the purely abstract in evolution of music.

For the heirs of Ives and Varèse, the history had reached a watershed. Starting with a sound newly liberated from traditional cultural constructs, they turned to the elaboration of graphic or literary scores. Their experiments with the indeterminacy of certain parameters and with the integration of the principles of chance into the process of composition, gave ascendancy to the immediacy of sound – to its autonomous existence independent of the casual relationships of a given structure – by calling into question the relationship between composer, interpreter and auditor.

And yet it is not easy to dismantle form. It supposes a profound evaluation of the auditive memory; for the smallest recurrence or the slightest accidental alteration of a leading note will revive our structural expectations, creating an impression of dynamic forethought, short-circuiting that free-fall within the instant crucial to our perception of a music of free association.

Using a form of notation ever more precise, Morton Feldman (1926-1987) began to develop writing procedures designed to utterly confuse the formal consciousness of the auditor and his perception of duration. His aesthetic, stark in the extreme, considered “minimalist” by many, avoids any acoustical anecdote likely to orient the auditive memory.

Triadic Memories for piano solo is an exemplary work among his compositions. Completed on July 23, 1981, and dedicated to Aki Takahashi and Roger Woodward, the piece is Feldman’s longest composition for piano: it comprises more than 1100 measures, a good third of wich are graced with repeat marks1. But, more to the point, this is a piece wich reflects his most methodical meditation upon the disorientation of memory, as he himself explains2.

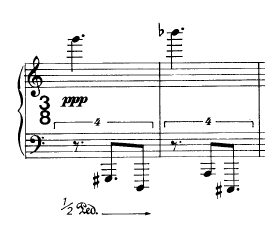

The entire score is written in triple piano, at times even quintuple piano – a veritable record, even for Feldman who only exceptionnaly indicates nuances greater than piano. The whole piece is bathed in the filtered resonance of the half inserted sustain pedal3. The rythm is rendered in quadruplets of quarter notes in measures of 3/8. The harmonic universe, built entirely on intervals of seconds, sevenths and augmented fourths, is in no way polarized. These elements, which rules out dynamic, rhythmic or harmonic accentuation, combine to form an acoustical continuum in perpetual movement, and a perfect suspension of time.

Another remarkable aspect of the piece is its extreme material economy: Feldman extracts the substance of more than an hour of music (at least in our version: no tempo is indicated!)4 from a two-bar module. These few notes, set in extreme registers of the piano, define at one and same time the ambitus – or melodic compass of the piece -, its hesitating rhythm and the intervals in the bass which will generate by successive developments and simplifications all the harmonic and melodic states of the work. All these material modifications (the changes in tessitura, the everincreasing number of superpositions of intervals, the aggregation of chords, the focalization, the sketching of melodic forms, etc…) are effected almost imperceptibly by means of varied repetitions, so that, in principle, the exhaustion by iteration of one state of matter gives birth to the next. And yet, because they are removed from any perceived chronology, the occasional incursions… the echoings of anterior sections or indeed rough sketches of future states… render a basic process which already favors the associative imagination, totally inaccessible to the memory.

It is these elements then… the timelessness, the material economy, the free use of repetition, the intermingling of sections… that slow down the process of dissolution, and, by, prolonging the final outcome for an inconceivable length of time, plunge the listener into the immediacy of pure perception, free from all formal preoccupations.

This is music that has no conclusion. It is simply reclaimed by silence from whence it is issue. And when it does, in due course, fade away, we are left there, listening to the minute rustlings of the instant… Unless, deaf for an hour to the beauty of this poetry without a story, to this abstract painting of time, to this recognition of the bankruptcy of progress, one refuses to be won-over by the descrete demands of this contemplative creator.

Jean-Luc Fafchamps, Summer 90.

About the second recording (Sub Rosa, 2010)

1. As explained in the introductory notes for my second recording of Triadic Memories, I ignored, at the time of this introduction, that Universal Editions’ first released of the score forgot to precise the number of time those bars have to be repeated…

2. “The question of scale, for me, precludes any concept of symmetry or asymmetry from affecting the eventual length of my music. As a composer I am involved with the contradiction in not having the sum of parts equal to the whole. The scale of what is actually being represented, whether it be of the whole or of the part, is a phenomenon unto itself.

This reciprocity iherent in scale, in fact, has made me realize that musical forms and related processes are essentially only methods of arranging material and serve no other function than to aid one’s memory.

What Western musical forms have become is a paraphrase of memory. But memory could operate otherwise as well. In “Triadic Memories”, …, there is a section of different chords where each chord is slowly repeated. One chord might be repeated three times, another, seven or eight – depending on how long I felt it should go on. Quite soon into a new chord I would forget the reiterated chord before it.

I have reconstructed the entire section: rearranging its ealier progression and changing the number of times a particular chord was repeated. This way of working was a conscious attempt at formalizing a disorientation of memory. Chords are heard without any discernible pattern. In this regularity there is a suggestion that what we hear is functional and directional, but we soon realize that this is an illusion; a bit like walking the streets of Berlin – where all the buildings look alike, even it they are not.” Morton Feldman, “Crippled Symmetry”, Cambridge, Mass. Autumn 1982

3. I correct here the erroneous translation in “soft pedal” of my French “demi-pédale” which appeared on the booklet of the cd.

4. I wasn’t wrong anyway: no version lasts less than one hour and most of them last more than mine.